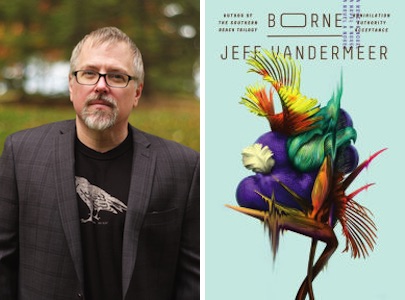

Jeff VanderMeer is a master of combining ecological concerns with a dark, weird speculative fiction. His Southern Reach Trilogy followed an uncanny event that created “Area X”, and the subsequent expeditions to explore the region, mining Nature itself to find the beauty and horror that comes with a radical shift in ecology. His latest novel, Borne, takes us to a future city, where people attempt to carve out lives after decades of societal collapse and environmental upheaval—you can read Niall Alexander’s review here. Rachel, a young refugee, scavenges for food and tech in order to survive with her partner, a former biotech engineer named Wick. Rachel discovers a particularly mysterious biotech while scavenging, and rather than turning it over to Wick’s experiments, she keeps it, names it Borne, and raises it like a child. Hilarity ensues, as does heartbreak, terror, and musing on the nature of survival and humanity’s role on Earth… and that’s all before you get to the skyscraper-sized flying bear.

VanderMeer is currently on a book tour for Borne, but he graciously took time to answer a few of my questions about the novel, and to discuss his love of the environment and the “New Weird.” He also shared a video of the Florida coastline that inspired Area X.

Leah Schelbach: First, I’m borrowing a question from a conversation between authors Amy Gall and Sarah Gerard: If Florida were a monster, what monster would it be?

Jeff VanderMeer: Some kind of weird chimera, perhaps because the state is so many things, so different in its various parts. South Florida, Central Florida, and North Florida could never be mistaken for each other. Each has its quirks and attractions. I like North Florida because it’s much wilder than the rest of the state.

LS: I feel like you and Lidia Yuknavitch and a few other writers are working to engage with climate change, and with humans’ disregard for the planet we live on. Would you say that you’re working from hope, or anger, or simply from a sense that it’s vital to confront our current reality?

JV: I don’t know how you escape the essential problem of our current existence: living beyond our means, on borrowed time. If you don’t feel it as a throbbing beat at the back of your brain, you must be more shielded from it than most people or have less empathy. People and animals are dying in the thousands if not many more due to climate change right now and due to the trashing of our planet. So it’s probably, hope, anger, and responsibility. But I’ve been writing about animal life and the environment since the late 1980s in my fiction. Sometimes, to be honest, as I’ve been tagged with different labels through my career, it’s been frustrating as I think I’ve been pursuing my own path and just passing through various territories as I approach the subject of ecology and nature from different vantage points, but always with many of the same themes.

LS: You’ve discussed hyperobjects in several interviews (I read Mord especially as a hyperobject who inspires feeling of incredulity, panic, and sometimes a sort of hysterical humor in people who see him) and this isn’t really a question, but I’d love it if you could talk about the particular challenges of trying to write about a concept that’s so large and important that people can’t look at it directly.

JV: Mord’s definitely a hyperobject. He’s very literal and real, but also a little like the freak storm on the horizon or the missile that explodes and levels a city: the unexpected force that rips away the world you thought you knew in a blink of an eye. In some situations, that suddenness is the killing thing—that everything you knew is gone—and it might as well be as if a huge psychotic bear flew toward you from the horizon. Just as inexplicable and impossible…and yet it has happened.

LS: Related to that, I ended up seeing Borne as a riff on a Christ/martyr character—a killer who doesn’t want to kill, and who realizes that he’s uniquely suited to perhaps save humans and animals. How did you develop his character during your writing process?

JV: I’m an agnostic trending toward atheist and resist in particular Christian interpretations and imagery. But I do think a certain Dickens’ tale had an effect on writing Borne as well as a meditation on nature versus nurture, although as biotech the deck is stacked in that regard. Definitely the idea of sacrifice and what you sacrifice for those you care about is central to the novel.

LS: Do you see Borne as a successor to your Southern Reach trilogy, or more as a departure?

JV: Area X was more about pristine wilderness and Borne is about ecology in urban spaces, especially in places we think of wrongly as broken or render invisible because we don’t want to think about. I also wanted to explore a situation where a multinational has come in and stripped resources from an area, and what resilience means in that context. And while the Southern Reach was about in part the lack of ability of characters to connect, Borne is about characters trying very hard to connect. People who are trying to be their better selves even while in extreme situations.

LS: I remember reading that you were inspired by the storytelling of Hannibal—my pick for greatest TV series of all time—what were some other influences as you wrote Borne?

JV: Yes, the storytelling the end of season 2 of Hannibal was genius-level and I thought about translations into fiction. Angela Carter and her flying woman in Nights at the Circus and Shardik in the novel of the same name by Richard Adams definitely come to mind. And this novel is much more influenced by comics and anime in general than my past work.

LS: Where did the character of Rachel come from, and why did you decide Rachel was our guide to this world rather than Wick, or The Magician?

JV: Rachel, to me, is the most interesting perspective in that in the end she has the most to lose of anyone and she is the one who also tries hardest to keep it together—whether it’s her relationship with Wick or with Borne. She has a limitless capacity to adapt, to pick herself up off the floor when things get tough, and at the same time she decides to trust in Borne despite being wary of trust. All of this made her fascinating to me. She’s also much less reserved and laconic than Wick, and I’d already written someone more reserved in the character of the biologist in Annihilation.

LS: Sarah Gerard closes her book, Sunshine State, with a list of her most significant encounters with Florida wildlife – could you talk about experiences that have given you new perspectives on how you write nature?

JV: Being charged by otters and wild boars, stalked by a Florida panther, and jumping over an alligator have certainly been memorable experiences. Some more comic than others. Each has a different way of coming through in the fiction. But the biggest thing, really, is that when you hike a lot in the same places, you eventually fade into the landscape and into the moment, and there is no greater gift to a writer than to be lifted so out of your own head that you’re almost floating and not a body at all…and in those moments the best ideas come into focus, unbidden and yet there they are, sudden and complete. So I’m grateful for that.

LS: Nnedi Okorafor has talked about a jellyfish who inspired her novella Binti. Did any specific creatures inspire the character of Borne?

JV: I definitely thought of cephalopods, with their neurons distributed throughout their bodies, and sea anemones, and even sea slugs. There are some beautiful creatures in the ocean that seem very alien at the same time.

LS: You’ve been a champion of the idea of the New Weird—where do you think the New Weird will/should go in the future?

JV: I kind of laugh when New Weird comes out into the light again, since it’s often kept in the basement in a cabinet with a broken, rusted lock. I’m a champion of the unique voices I love in fiction and labels one hopes slide off so readers can see the work entire and not just the part with the label attached. If there is a brightness that emanates out of writing I adore it is something without a name that makes me drunk with the beauty and sadness and rightness of it. That’s all I want from fiction—to be annihilated and taken over by. What it’s called otherwise, I don’t much care about.

Finally, VanderMeer has taken a crew to the marshes near Tallahassee, Florida, for a short film, “Life in the Broken Places.” Here the author talks about Nature’s ongoing adaptation to urban spaces, and the importance of caring for our environment.

Borne is out now from Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.